If you’re reading this, it's likely you've asked yourself the very question posed in the title. Perhaps it was on a long, lazy drive upstate, late afternoon fishing on the lake, or an early morning hike in the canyons. Well fear not! That momentary glance, that grainy phone video, the out of focus binoculars that constitute your body of evidence are enough to give pivotal clues. From that information, we can successfully track down the avians that elude us. This is nowhere near exhaustive - rather, it is an attempt to provide a starting point for discussion and consideration.

Some particularly useful concepts will be addressed in 4 key points:

To begin with identification, we have to plant our feet somewhere. Depending on confidence level and familiarity with the local ecology, your approach will really vary. As with any truly worthwhile craft, the study of the natural world is a constantly evolving and reiterative process. It’s unlikely you’re making a groundbreaking discovery every time you go out to bird at your local marsh, meadow, or park - so have fun, and try to remember that every time you get a chance to go out birding it's a success.

Habitat is a defining aspect of animal identification. I know that when I’m walking around Sepulveda Basin or Griffith Park in LA, I’m not going to see Northern Cardinals, Blue Jays, or Black-capped Chickadees - their distribution tells me so, with confidence. However, when I’m visiting family back home in Michigan, I expect these birds as common visitors to the feeder. California enjoys a remarkable amount of diversity and variation in its wildlife, and when I am identifying areas that I believe will provide me a profitable morning of birding, I look for diverse transitional habitat zones.

Here are some examples of the kinds of environments that I have found to encourage biodiversity, particularly when found nearby to one another. These were all taken within the Hahamongna Watershed Park, and yet they boast radically different conditions that are suitable for radically different species - in concert, they produce rich, diverse, healthy ecosystems with a wide array of wildlife.

This changes depending on where you are - around Mammoth, this means looking for areas that feature meadows, coniferous forests, rocky slopes, and tranquil high alpine lakes with an active inlet. Around LA, I like areas that feature a water source (seasonal or otherwise) that feeds the growth of surrounding alder, cottonwood, and a variety of sedge grasses and reeds, extending into chaparral-scrub, and settling into oak groves that provide a canopy.

In Michigan, these environments will look very similar - look for transition zones between meadows and creeks, which are often made all the more obvious by the line of alder, birch, and willow that will grow along the water’s edge. Hills and ravines can be great, too - the banks can provide great habitat for nesting birds, making these fun locations to peruse during the “shoulder seasons” of spring and fall.

These environments are teeming with the ingredients for life, and when you atomize their individual parts, you will notice more, and more, and more details about why you find birds where you find them. The more variety in your environment, the more variety in the species you’ll encounter. If you stick to this rule of thumb when exploring, or researching where to explore, you’ll generally be setting yourself up for success.

So, now you have an idea of how to set your expectations, and you have an idea of what kind of locations might provide a satisfactory amount of bird activity - let’s consider how this can be useful for identifications.

You’re in the canyons up near Vazquez Rocks, and you see a large bird with dark feathers circling up above you in the sky. In your excitement, it might be tempting to jump to conclusions.

“It’s a Bald Eagle! Yippee!”

However, considering the habitat, it might be a good idea to take a step back. Bald Eagles need water - they habitually build their nests in old-growth trees along the water's edge, in order to have a steady diet of fish to feed on. Visitors can attest - beautiful though it may be, Vasquez Rocks is dry as a bone. Scanning the horizon, it is plain to see that there are no tall trees, canopy cover, or large branches. Nor is there an abundance of mammalian and aquatic life.

What we initially thought was a Bald Eagle… was much more likely a Turkey Vulture, or a very large Common Raven with the sun at its back; other birds of prey in the region include the Red-shouldered hawk, Red-tailed hawk, and Golden Eagle, all of which are more likely than a Bald Eagle.

Like other birds of prey, Bald Eagles have exceptional eyesight, but they are uniquely adapted to hunting near waterways; I’ve recorded multiple videos of 30+ seconds in length of eagles hovering above the surface of our lake before plunging down and returning with a fish in their talons. Think of how a Kestrel will hover in midair before diving - now imagine a Bald Eagle doing that!

In short: environment is overwhelmingly important in determining expected range, which we base upon our knowledge of what is required for their survival as a species. Sometimes, expected range doesn’t just incorporate where sightings have been, but where they could be, based on these benchmarks. So our first ID attempt might not have been right, but that’s okay - let’s explore some other tools!

You’ve been walking in a field for what feels like hours, the hot sun beating down on you like you owe it money. You’re desperate to stop for rest, and you look around for a place to do so. Your eyes fall on 3 features: a large, shady, solitary tree; a sizable boulder in the middle of the field; or, the dry soil right below your feet - and boy, are your dogs barking. How do you decide?

In the same way that you might be drawn to take shelter in one place or another on your own adventures, birds are constantly doing the same, and their behaviors and physiology have adapted to complement the places they position themselves in their environment. An easy to intuit example: empidonax and myiarchus flycatchers.

As their name suggests, flycatchers specialize in snagging flies out of the air, and they are a passerine - or perching - bird, so they will often find a conspicuous perch from which they can assess their targets. They will catch and collect the flies, bringing them back to their perch or the nest.

If you’re looking to better understand flycatchers, try to find a Black Phoebe on your next walk in California, or an Eastern Phoebe in Michigan. They’re exceptionally common in a variety of habitats, thriving best in riparian settings and meadow clearings that provide healthy breeding ground for insects. Black Phoebe are defined by their dark brown to black feathers on the back, head, wings, and tail, with a white or light tan chest and belly that stands out against their otherwise dark silhouette.

Observe how they position themselves on a low perch, scanning the environment actively as they seek out a snack, and how frequently they dart out to haul in their insect prey. They stay low to the ground, because the bugs are in greatest abundance in these areas, and the hunting is most profitable with the lowest amount of energy expended. Fighting air currents and gusts at 50 feet up, trying to find a single bug getting tossed around, is not an effective way to spend one’s afternoon.

Pictured: a Black Phoebe, perched on a trash can (!) beside a meadow. This little one was darting out and catching flies, returning to its perch each time.

Check out how these Ash-throated flycatchers have positioned themselves in this meadow. There was an abundance of cottonwood ringing the area, and the meadow itself was teeming with bugs - these little guys were hanging out together in a group of about 5 or 6 on these felled branches.

Many flycatchers, when actively seeking out their catch, can be seen on a relatively low perch. One strategy that I use when trying to identify birds, particularly when I’m zeroing in on a birdsong or call that I’ve just heard, is to divide up the space that I’m examining into different sections. When I’m looking at larger trees, I have found it helpful to divide the branches into three sections vertically - Top, Middle, Bottom - and two sections horizontally - Left, Right. What this does is helps me to triangulate the sound of a bird call as I’m hearing it - I can treat each section of the tree as its own ‘zone’, check off what I’m hearing in each zone, and prioritize the species that I want to target based on their position within the tree. When I hear something appealing on my birdwalks, I position myself accordingly in order to be more successful. Birding doesn’t have to be a blind process!

Furthermore, developing a baseline knowledge as to how and why different birds prefer different places really can help us so much! Tiny warblers like the Yellow Warbler will be active but inconspicuous, much more frequently heard than seen. Big, bold raptors like Red-shouldered and Red-tailed hawks will find a nice perch at the top of the tree, where they have clear sightlines and an easy takeoff lane. As we covered, flycatchers will find low to medium perches that give them a nice view of their hunting grounds. Herons, egrets, cranes, and shorebirds like to stalk along the edges of the waterline. Some ducks are dabbling ducks, some are diving ducks; the specific classification of passerine has its own scope of birds that it covers that truly exemplify the 'perching' behavior, but the very concept of a perch can be useful in abstracting and think about how and why birds are where they are.

Compare the difference in how this Yellow Warbler and Red-shouldered Hawk position themselves when calling out - one can afford to be much more conspicuous!

During their respective breeding seasons, many birds will display much more prominently, finding a more exposed position than usual to sing and look for mates. When fledglings are beginning to leave the nest, they will often be much less stealthy than their parents - their inexperience gives them away.

In short: within the same habitat, not all perches are equal. The choice of a perch, and the behaviors expressed in that position, serve as strong identifiers when deducing the identity of your feathered target. Especially when you don't have a lot to work with, think critically and abstractly about not just where your bird is, but the nuance of how it occupies that location.

Time works on different levels for birds, just as it does for us! The 24-hour daily cycle shapes bird behavior on an immediate, ‘micro’ level, while the 365-day yearly cycle dictates bird behavior on a more grand, ‘macro’ level. Both are inextricably linked to when and where birds are where they are! If you’re looking to track down a specific species, then taking into account the observable recorded patterns is the right place to look.

Birds operate on very predictable schedules - there are some birds that you will become hard-pressed to find past a certain hour in the morning, despite what seems reasonable to you or I. While 7:15 AM might seem early enough, this can often mean arriving after the peak of songbird activity has already occurred in more open habitats like chaparral scrub, desert scrub, cliffside embankments, and other scrabbly, exposed terrain.

Particularly in desert and alpine settings, the window for bird activity tends to close earlier and earlier the hotter and hotter it gets - during the heat of summer when temperatures are regularly above 90-100°F, it might only be a few minutes at or before dawn before birds begin their retreat back into cover.

As just another component of how you select your targets, it becomes easier over time to begin naturally incorporating these ideas into your approach to the hobby. Going out birding for the first time is a big deal! And the more you do it, the more natural it becomes.

I’ve found that between the times of 5:00 AM-11:00 AM in the morning and between 6:00 PM-9:30 PM I tend to see and hear the greatest number of birds. Within these windows, there are different species that we can track down and try to provide ourselves with the best chance possible of seeing.

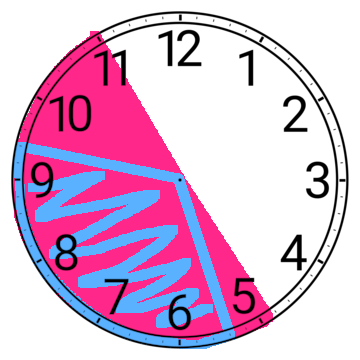

Here’s a graphic of what I’m referencing:

Pink is morning, blue is evening. Kinda crazy how the times can be visually divided so cleanly, no? Birds still come out during the unmarked patch, but the high points in activity occur only on one 'half' of the clock.

As it turns out, this is tested stuff! It isn’t just a coincidence - in fact, there is extensive research that has been done and is being done about how environment can alter activity, studied down to the exact minute and second - here’s a link to an example of one work with some really cool data.

⊹⋛⋋( ՞ਊ ՞)⋌⋚⊹ study conducted on bird song in alpine environments ⊹⋛⋋( ՞ਊ ՞)⋌⋚⊹

As a historian and an archivist, I love making lists, tracking data, keeping notes and tabs. One of the cool things about naturalist hobbies like birding is that this naturally comes baked in, and with easily available technology you can set about making an archive from your own materials. I can look across all of the pictures that I've taken and find patterns among them based on highest and lowest frequency of sightings throughout the day - and this is just the start! There are so many incredible ornithology resources out there, both local and national, that can make this hobby even more fun than it already is.

Nobody likes waking up before sunrise - yet it’s the very fact that nobody likes to wake up before dawn that makes it such a good time for birds and fish to be out. Bugs are becoming active, the light of day is growing but still low enough to provide a veil, and their circadian rhythm is sending biological signals throughout their bodies to get up, get moving, and get some breakfast, just like ours do in the morning.

As previously mentioned, there are some species that follow these clocks strictly. Whether you're setting lifer targets, planning out a day hike, or setting off on a fishing trip, you don't have to force yourself to bear the full heat of day in the pursuit of a good time - the birds and fish won't be out, so why should you?

Strive to find a balance! If you only have time to go for a 30 minute walk in the afternoon on a hot day, do it! It never, ever means that you're wasting your time - it's all about expectations. Shape your expectations around the availale data, and there won't be any pressure, nor fear of missing out. Any amount of time that we have to spend in nature is worthwhile!

With this in mind, let's jump back into our ID!

You’re walking the perimeter of a small backcountry lake as sunrise fast approaches, the growing din of insects rising steadily around you. You’re seeing some birds, the numbers still low. Suddenly, you see a flash out of the corner of your eye, and you snap your head - there’s a bird in front of you! It’s big! It has a white head! It just plunged into the water and is now flying off with a fish!

“B-b-b-bald Eagle!!!!”

Hold your horses - how can we be sure? The head was white, true. It had broad brown wings; massive bright yellow talons; a beak shaped like a velociraptor’s claw. We’re getting somewhere…

The obvious answer, of course, is that being in the right place at the right time doesn’t guarantee anything. If you set out with birding as your goal, you might have birds in mind that you want to see when you’re exploring - be careful to avoid confirmation bias in your IDs, wherein you let your desire to see a certain bird override your sense of logic and the evidence in front of you.

Back to the ‘Bald Eagle’ - knowing that we can’t rely solely on just habitat and behaviors, we begin to look at the actual physical features of the specimen itself. From the details we listed above - large wingspan, pale head, curved yellow beak, and long talons - we know that we’re dealing with a bird of prey, which will include birds like raptors, falcons, eagles, and owls. In the US, some common genera that these birds are grouped into are: buteo; accipiter; aquila; haliaeetus; falco; and the various genera of owls. When looking at the species within each genera, you’ll find some commonalities between them - buteo have wings better designed for soaring, while accipiter have short, broad, agile wings for tight corridors and dense trees; falcons employ fast, short wingbeats to change direction and stay in constant motion in the air, divebombing their targets after hovering in place.

So, let’s take everything in concert. We have a bird of prey with a large wingspan, gnarly talons, sharp beak, and a pale head. We saw it near the surface of the water catching fish, so we’re looking for a species that hunts and maybe even nests near the water habitually. We can rule out accipiter and buteo, as the size, coloration, and habitat don’t align. In the same way, let’s discard falco - the size of the bird we saw, relative to the sizes of the falcons in North America, make it possible.

Alright, back to it - what about aquila? Nothing doing again, unfortunately. The only ‘true’ eagle in North America, the golden eagle, much prefers open grasslands, rolling plains, and long sightlines to soar above. Still, we’re doing great, we’ve whittled down to fewer options: owls (bubo, tyto, strix), pandion, and haliaeetus. Birds from the genus strix are wood owls, so we can count those out right away - too small, not the right plumage. The genera bubo and tyto cover a range of owls, which can indeed grow quite large! They have large talons, a curved beak, and an imposing wingspan, and they can often be seen hunting near water at night, which also seems promising. However, let's take our two best options - the Great Horned Owl, bubo virginianus, and the American Barn Owl, tyto alba - and interrogate these features.

The Great Horned Owl has a wingspan that can reach up to 60 inches, and stands 18-24 inches in height. The American Barn Owl has a wingspan in the range of 38 to 44 inches and stands 13-14 inches in height. The Great Horned Owl has mottled brown feathers that give it a woody appearance, allowing it to easily blend into its surroundings. It has big talons and a hooked beak - but the proportions aren’t what we’re looking for, nor the plumage. The American Barn Owl has a tan body with some mottling, and a white head and face with a cupped appearance. While the color of the head might be one factor that aligns, everything else - the size, shape, and colors - all tell us that these can’t be our bird, either.

So, we move to our last realistic remaining options - pandion and haliaeetus. The only member of the genus pandion in North America is the Osprey - commonly known as the ‘fish hawk’ - can be found on many bodies of water of varying size. In Michigan, I see Ospreys along the Huron, Black, and Cheboygan rivers, just as I see them at Lake St. Clair, Lake Huron, and Lake Erie. If there are fish, they thrive. Their markings are highly distinctive, though, and will make it obvious to the observer whether or not they’ve seen a bald eagle. Look for the brown on its cap and face, and the dark flight feathers juxtaposed against a pale white body, to help differentiate from other large sea-eagles. Now to make things confusing - the Osprey is not one of the two actual sea-eagles of the genus haliaeetus (lit. sea-eagles, or osprey). Instead, this is where we find the Steller’s sea eagle, haliaeetus pelagicus, and… the Bald eagle, haliaeetus leucocephalus! The Steller’s sea eagle can be discounted as an ID, as these are generally only seen as vagrants in the westernmost reaches of the Alaskan coast, which make their way over from their more common range in Siberia and the Palearctic. In late 2021 and early 2022 there were several outlier sightings in Massachusetts and in Maine, with these being the FIRST documented sightings in the 48 contiguous states ever. So, let’s disregard the species that only has a handful of historical sightings in the lower 48 - who are we left with?

That’s right - your prized bald eagle!

And all things considered, that wasn’t so bad.

Through identifying proper habitat, behaviors, time, and size, we were able to differentiate our bird from all the others - and there are a lot! But when we take into account not just what is possible but what is most probable, it all becomes much easier to tackle.

Bonus image: one of the bald eagles that roosts next to the family house in Northern Michigan, whom I have affectionately nicknamed LeBron James on account of possessing similar all-American qualities.

All of this may have seemed a bit obvious, no? That’s because you’re an observant individual! The best thing about birding is the connection to nature that you develop and the subsequent positive ecological impact you can have as an individual who grasps the full breadth and importance of the collective balance of our ecosystems; the second best thing about birding is that asks nothing of you, requires no investment at base level, and has no barriers to entry.

By approaching birding with an intentional, investigatory attitude, you enrich your own experience and the experiences of all the creatures you encounter. Every meadow you walk through, you’ll step a bit more carefully; every creek bed, you’ll be looking underfoot; when you comprehend every element of your environment as a potentially integral piece of that system, you walk softer, listen closer, and care more. Nature proceeds with a mindless appetite, liable to swallow any species whole in its lurch, and with the radical free will that we have been given, we should be so gracious as to not make that process any more difficult.

Please, please reach out if there is any information printed here that conflicts with your amateur or professional opinion! I am a lifelong amateur birder and naturalist, and I’m always amenable to correcting my mistakes and learning something new. I worked at the Museum of Natural History while I was in university and grew up volunteering at our local nature centers and visiting state and national parks, and I’ve always been so grateful for the opportunity to continually learn and grow through my endeavors. I'm always open to compassionate discussion and constructive criticism in the interest of being a better hobbyist and educator.

contact:

![]()